When the Pictures Learned to Walk

The history of video editing

Today you can sit in a co-working space, a hostel kitchen or a tiny apartment, open your laptop and edit a full documentary in DaVinci Resolve or Premiere Pro.

A little more than a century ago, none of that existed. Moving images were a laboratory experiment, and “editing” literally meant cutting and gluing strips of film by hand.

This article takes you through the history of video editing – from the first moving images to digital non-linear editing – and what all of this means if you earn your living (or build your side project) as a location-independent editor or filmmaker.

Why this matters if you edit from a backpack

- Understand your tools: from destructive film cuts to non-destructive timelines – and what that means for your project structure today.

- Explain your value: you’re not “just cutting clips”, you’re shaping time, rhythm and story for clients who are often far away.

- Design better workflows: when you know how we got here, it’s easier to build remote-friendly, resilient setups that still work on the road.

1. Before editing: when images first started to move

At the end of the 19th century, inventors were still trying to answer a basic question:

How can we make a sequence of still photographs look like continuous motion?

In the United States, Thomas Alva Edison’s team developed a motion picture camera called the Kinetograph and a viewing device known as the Kinetoscope. Around 1891, Edison secured patents for this camera–viewer setup, including what would later become the standard 35 mm film width.

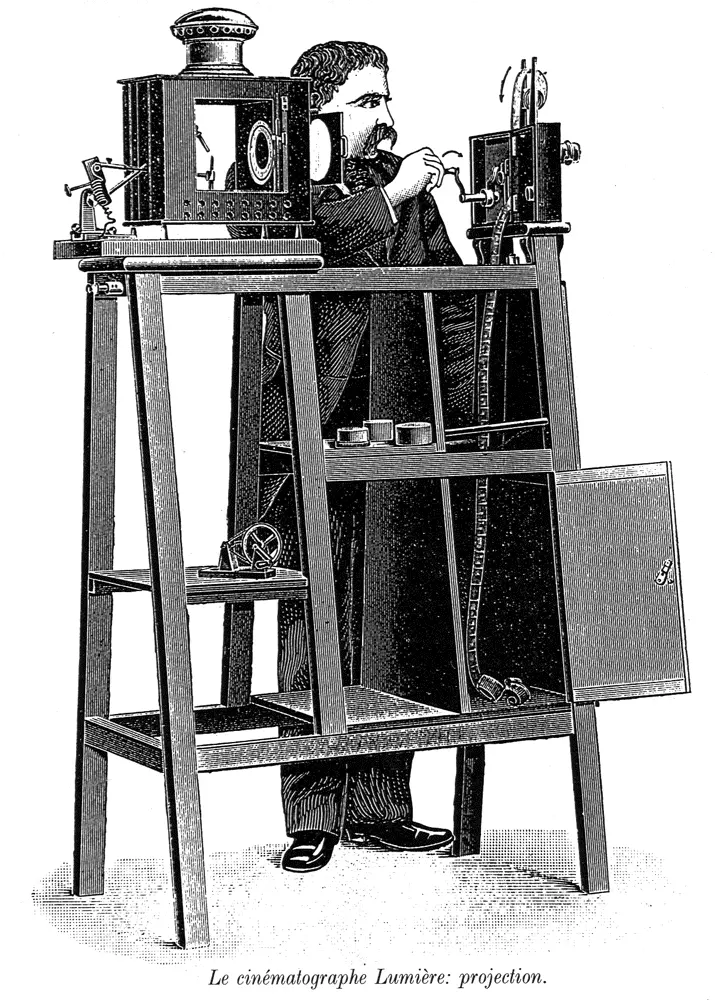

In France, Auguste and Louis Lumière created the Cinématographe, a device that could function as a camera, printer and projector. With it, they presented short films such as Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory in 1895 – one of the earliest publicly screened motion pictures.

In this early phase, there was almost no editing. Films were extremely short and usually shot as a single, uninterrupted piece. But the core ingredients of editing were already present:

- a way to capture motion

- a way to project it to an audience

The idea of arranging multiple shots into a meaningful sequence came a little later.

2. Scissors, tape and film cement: cutting film by hand

As filmmakers wanted to tell longer, more complex stories, a new problem appeared:

How do you connect separate shots so they feel like one continuous experience?

The solution was as physical and hands-on as it gets:

- Editors worked with celluloid film strips on large editing tables.

- They marked in- and out-points directly on the film.

- Then they cut the film with scissors or a blade and joined it with tape or film cement.

From this manual process, the basic grammar of film editing emerged:

- Establishing shots to introduce a space

- Close-ups to emphasise emotion or detail

- Shot–reverse shot patterns for dialogue

- Match cuts to keep motion or direction continuous across cuts

Every decision was destructive: once you cut into the negative and glued things together, it was tedious and sometimes impossible to go back. That’s one reason why early editors were extremely precise and cautious.

For Nomadic Filmworks (and anyone editing today), this is the origin of something we often take for granted: the idea that you can deliberately shape time and attention through cuts.

3. When films started to talk: editing with sound

In the 1920s, another revolution transformed editing again: synchronized sound.

In 1927, The Jazz Singer premiered – a film that mixed silent sequences with sections of synchronized dialogue and music. Its commercial success is widely seen as the breakthrough of sound films, the so-called “talkies”, and the beginning of the end for purely silent cinema.

For editing, this changed the rules:

- Picture and sound now had to stay in sync.

- Dialogue created a new kind of rhythm that editors had to respect.

- Cuts could not simply follow the visuals; they also had to follow speech, pauses and musical structure.

Editing became even more of a story craft. Editors were not only deciding what the audience sees, but also when they hear a word, a breath, a pause.

If you edit interview-based documentaries, branded content or talking-head videos today, you are still working under these same constraints – just with far more flexible tools.

4. From film reels to magnetic tape: the era of linear video editing

For many decades, film remained the main medium for production and editing. That changed when television and videotape entered the scene.

In 1956, Ampex introduced one of the first practical videotape recorders for television, using 2-inch magnetic tape (the “Quadruplex” format). Broadcasters could now record and time-shift programmes without shooting everything on film.

This launched the era of linear video editing:

- Material was recorded on tape.

- Editors used two or more tape machines (player and recorder).

- To build a programme, they copied each shot in order from one tape to another.

The term linear describes the main limitation: editing happened in the same sequence as the final film. If you wanted to insert something earlier in the programme, you often had to redo large parts of the edit.

Typical characteristics of linear editing:

- Timecode became essential to navigate and plan edits.

- Mistakes could be expensive, because each new version required more tape and machine time.

- Complex re-edits were slow and often avoided unless absolutely necessary.

Compared to film, videotape made recording and playback easier and cheaper, especially for TV. But for editors, the workflow was still rigid and unforgiving.

5. Non-linear editing: when timelines changed everything

The next major turning point was digital.

In the late 1980s, computers became powerful enough to handle compressed video. In 1989, Avid released its first Media Composer, a digital non-linear editing (NLE) system that ran on Macintosh hardware.

This was a qualitative shift:

- Instead of recording a programme line by line onto tape, editors could now work in a timeline inside a software interface.

Key differences of non-linear editing:

- Original clips stay untouched on disks.

- You arrange them virtually in a timeline – like a playlist of in/out points.

- You can move, trim, insert or delete clips anywhere in the sequence without re-recording everything.

In the 1990s and 2000s, tools like Avid Media Composer, Adobe Premiere Pro, Final Cut Pro and later DaVinci Resolve became industry standards for film, TV and online video.

For working editors, this meant:

- iterative cutting (try a version, duplicate it, try another)

- tighter integration of color grading, graphics, sound design and VFX

- easier collaboration via project files, shared media and later shared storage

If you edit today, chances are you live almost entirely in this non-linear world. Linear editing still exists, but mostly in niche or live-broadcast scenarios.

6. Online video, remote workflows and AI-assisted editing

The story of video editing does not stop with NLE software.

With the launch of YouTube in 2005 and the rise of broadband internet, video editing became a mass skill. Anyone with a camera and a basic editor could publish to a global audience.

This changed the context of editing:

- Formats multiplied – from long-form documentaries to 10-second vertical clips.

- Feedback loops became shorter: upload → comments → quick re-cut → re-upload.

- Distribution moved online: Vimeo, YouTube, social platforms and later streaming services.

For digital nomads and small studios, this opened real opportunities:

- You no longer had to live near big production hubs.

- Clients could send footage via cloud storage.

- You could deliver cuts from almost anywhere with a stable connection.

Today, there is another layer on top: AI-assisted workflows.

- Tools that auto-transcribe dialogue and generate subtitles.

- Assistants that create rough selects based on faces, keywords or scene changes.

- AI-driven color matching, noise reduction and smart upscaling.

At Nomadic Filmworks, I use these tools where they genuinely save time – but the core decisions still happen in the timeline: pacing, structure, what to show and what to leave out. Machines can accelerate technical tasks, but they do not replace your judgement about what a scene should mean.

7. Key milestones in the history of video editing (quick overview)

For readers who like the timeline view, here is a compressed overview of some important points:

- 1891–1895 – Early motion picture devices (Kinetograph/Kinetoscope, Cinématographe); films are extremely short and essentially unedited.

- Early 1900s – Physical film cutting becomes common; editors develop techniques for continuity, cross-cutting and montage.

- Late 1920s – Sound films (“talkies”) go mainstream; editing must respect picture and sound rhythm together.

- 1956 – Videotape recorders enable linear tape-based editing for television.

- Late 1980s / 1989 – Avid Media Composer and similar systems bring digital non-linear editing to professional post-production.

- 2005 onwards – Platforms like YouTube turn video into a global, always-on medium; editing becomes a widespread skill, not just a specialized job.

From there on, the timeline branches out: 4K, HDR, smartphone cameras, AI tools, remote workflows and more.

8. Practical lessons for editors who work on the road

If you are a digital nomad, freelancer or small one-person studio, the history of video editing is not just a nice trivia topic. It has very practical implications for how you work today.

a) You understand what your tools are really doing

Modern software hides a lot of complexity. Knowing that:

- film editing used to be destructive,

- tape editing was linear,

- and NLEs are non-linear and non-destructive

…helps you build smarter project structures:

- work with versions instead of overwriting your timeline,

- use proxies when your laptop struggles,

- design timelines in a way that future changes don’t break everything.

b) You can explain your value beyond “I know the software”

Clients sometimes see editing as “just cutting clips together”. When you understand the evolution of editing, you can position yourself differently:

- as someone who shapes narrative and rhythm, not just someone who presses export,

- as a partner who understands distribution formats (social, web, festival) and how they evolved,

- as a person who can bridge old and new – for example by integrating archival footage, analog material and modern digital workflows.

That’s exactly how I work with Nomadic Filmworks: not just as an “editor”, but as someone who helps clients turn raw material into stories that still feel human in a very fast, very digital world.

c) You can design workflows that suit a nomadic life

The shift from physical film and heavy tape machines to lightweight laptops and external SSDs is what makes location-independent editing possible in the first place.

If you know why:

- non-linear systems are so flexible,

- cloud sync and shared storage fit into that logic,

- and AI tools sit on top of existing editing paradigms,

…you can design your own stack more consciously:

- local editing when the internet is shaky,

- remote review when clients are in a different country,

- backups that don’t depend on a single device or location.

d) You stay grounded when tools change (again)

Tools will keep changing: new AI features, new formats, new platforms. Knowing where editing came from keeps you calm:

- the principles of storytelling remain,

- the core decisions of pacing and selection stay with you,

- software and hardware are “just” layers on top.

9. Conclusion: the history behind your timeline

The history of video editing is, in a way, the story of how we learned to structure time and emotion with moving images:

- from unedited glimpses of everyday life,

- to carefully cut film reels,

- to linear tape edits in TV control rooms,

- to the non-linear timelines we use on laptops all over the world.

As Nomadic Filmworks, this is the context I bring into every project: respect for where the craft comes from, curiosity for the tools we have today, and a focus on what matters most – stories that make sense to real people, wherever they watch.

Whether you’re editing from a dedicated studio or a temporary desk in a different city each month: every cut you make is part of this long evolution.

And that, to me, is the real magic behind a modern timeline.